Long/short funds sound like the investing equivalent of “having your cake and eating it too.” Go long the winners, short the losers, reduce market risk, and stroll into the sunset with smoother returns. In theory, it’s beautiful.

In practice, it’s often been… a group project where one person does all the work (the long side) and the other person (the short side) still wants equal creditwhile also eating your lunch money via fees.

This gap between the promise and the lived experience is exactly why the question keeps coming uppopularized by Ben Carlson’s classic A Wealth of Common Sense take: Why have long/short funds performed so poorly?

Let’s unpack the real-world reasons, using plain English, specific examples, and a few gentle jokes for emotional risk management.

What Is a Long/Short Fund (and What It’s Supposed to Do)

A long/short fund buys (“goes long”) investments it expects to rise and sells short (“goes short”) investments it expects to fall. Many long/short equity funds are net long overallmeaning they still have meaningful exposure to stocksjust less than a typical stock fund.

Key terms you’ll see (and what they actually mean)

- Net exposure: Long exposure minus short exposure. (Example: 80% long and 30% short = 50% net long.)

- Gross exposure: Long exposure plus short exposure. (80% long + 30% short = 110% gross.)

- Goal (usually): Capture some upside, reduce some downside, and make stock-picking matter more than market direction.

The pitch is often “equity-like returns with lower volatility” or “downside protection without giving up all the upside.” The problem is that those are two different promisesand many funds end up delivering neither consistently.

The Big, Boring Truth: Most Markets Have Been Unfriendly to Long/Short

If the stock market spends years trending upward, being partially hedged can feel like showing up to a marathon with ankle weightsby choice.

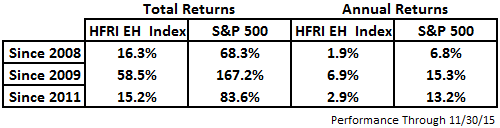

Since the Global Financial Crisis, long bull markets, concentrated leadership, and “risk-on/risk-off” trading have often made life harder for long/short managers.

But that’s just the backdrop. The real story is a stack of headwinds that add upfees, shorting costs, market structure, factor crowding, and the simple math of being less invested when markets rise.

Reason #1: The Math of Net Long Exposure Is Not Your Friend in Bull Markets

Many long/short equity funds run something like 40%–70% net long. That means when the market rallies, they’re automatically not fully participating.

A simple example (no PhD required)

Imagine a long/short fund is 70% long and 30% short. That’s 40% net long.

If the market rises 20% in a year and the manager’s stock picks are merely “fine,” the market exposure alone might contribute roughly:

0.40 × 20% = 8% (from net exposure)

Now subtract:

- the drag from shorts that are rising with the market,

- trading costs from running two books,

- higher expense ratios than plain-vanilla index funds.

Suddenly “the fund returned 7% in a year the S&P 500 returned 20%” doesn’t look like a mystery. It looks like… arithmetic.

Reason #2: Shorting Isn’t Free (and Sometimes It’s Not Even Cheap)

Short selling comes with structural costs:

- Borrow fees: You may pay to borrow shares, especially for hard-to-borrow names.

- Rebates/cash collateral dynamics: The economics of shorting can vary with interest rates and market plumbing.

- Short squeezes: Even if you’re “right” fundamentally, a crowded short can become a face-melting rally that forces covering at the worst time.

These costs matter because many long/short strategies get a meaningful chunk of their edge from the short bookyet the short book is the part with built-in friction. Research has shown that apparent “anomaly” profits in long/short portfolios can be heavily reduced or even eliminated once short-sale costs are included. In other words: the backtest was cute, but the borrow desk would like a word.

Reason #3: Low Interest Rates Quietly Removed a Return Engine

This is a sneaky one because it doesn’t show up in marketing brochures with fireworks.

Many long/short and market-neutral approaches hold substantial cash or cash-like collateral. When cash yields are near zero, that portion contributes little.

For years after the financial crisis, rates were historically low, which reduced the “background return” from cash balances and short-sale collateral.

When a strategy is built to be defensive and carry lower net exposure, losing that cash yield can be a real hit to long-term results.

Reason #4: “Risk-On/Risk-Off” Markets Made Stock Picking Harder

Long/short managers want a world where winners and losers separate based on fundamentalswhere dispersion is healthy and correlations aren’t all moving in lockstep.

But in many post-crisis stretches, markets behaved like a single giant trade:

When investors felt good, almost everything rose. When investors panicked, almost everything fell. In those regimes:

- correlations rise,

- dispersion falls,

- fundamental selection matters less,

- and hedges don’t always hedge the way you’d hope.

Reason #5: Momentum and Crowding Have Been Brutal to Many Short Books

A lot of long/short equity managers end up with shorts that cluster in certain “types” of stocks: weaker balance sheets, deteriorating fundamentals, overvaluation signals, or popular “story stocks” that look expensive on traditional metrics.

In momentum-driven markets, expensive stocks can get more expensive for longer than seems polite. If your short book leans against momentum, it can bleed for months. And when crowds pile into the same shorts, the exit doors get narrow fast.

The meme-stock era made this painfully visible: some heavily shorted names experienced explosive rallies, not necessarily because fundamentals improved overnight, but because positioning and flows overwhelmed fundamentals. Even “diversified” short books can get clipped if the same risk factors dominate.

Reason #6: Fees and Trading Costs Create a Higher Hurdle Than Investors Realize

Long/short funds generally cost more than traditional stock funds and vastly more than index funds. That’s not a moral judgment; it’s just the reality of running a complex strategy.

Why costs tend to be higher

- Two portfolios (long and short) mean more research, more trading, and more operational complexity.

- Shorting introduces borrow costs and additional transaction frictions.

- Some funds use derivatives for hedging, adding implementation costs and sometimes financing costs.

If the long/short manager’s skill adds, say, 2% of “gross value” in a year, a big slice of that can get eaten by expenses and frictions before you ever see it.

Meanwhile, your benchmark (a low-cost index fund) is jogging downhill with a tailwind and a 0.03% expense ratio.

Reason #7: “Liquid Alts” Constraints Can Water Down the Strategy

Many long/short products available to everyday investors live in mutual funds or ETFs. Those structures offer daily liquidity and strong investor protectionsbut they also limit what managers can do compared with classic hedge funds.

Common constraints include:

- limits on illiquid positions,

- risk and leverage controls,

- derivatives usage rules and reporting requirements,

- the practical challenge of running shorts in a daily-liquidity wrapper.

The result: some “hedge-fund-like” strategies end up looking like “expensive, somewhat-hedged stock funds,” which can be the least exciting category of all categories.

Reason #8: Investor Expectations Were Set Too High (and Too Vaguely)

Here’s the human part. Many investors bought long/short funds expecting one of these outcomes:

- “I’ll beat the market.”

- “I’ll get stock-like returns with bond-like volatility.”

- “This will protect me in the next crash.”

Those are not impossible outcomes, but they’re difficult, and they usually require very specific market conditions and exceptional manager skill.

When the market grinds higher for years, a defensive posture feels like “underperformance,” not “risk control.”

When volatility spikes, a hedged fund can still lose moneybecause hedging reduces exposure, it doesn’t guarantee profits.

So… Are Long/Short Funds “Bad”? Not Exactly. They’re Often Misused.

Long/short funds can have a place, but that place is usually not “core replacement for a stock index.”

They’re more often a satellite allocation meant to diversify equity risk, reduce drawdowns, or deliver a different return pattern.

Questions to ask before using one

- What’s the typical net exposure? If it’s 50% net long, expect meaningful equity correlation.

- What’s the goal? Lower volatility? Crash protection? Absolute return? These aren’t the same.

- How does the short book work? Fundamental shorts, factor shorts, hedges, or a quantitative screen?

- What are total costs? Expense ratio, trading, financing/borrow costs, and tax implications.

- What market environment helps this strategy? Higher dispersion and reasonable cash yields often help; high correlations and momentum melts can hurt.

When Long/Short Funds Tend to Look Better

While the post-crisis era was often hostile, conditions can shift. Environments that may be more supportive include:

- Higher dispersion: more separation between winners and losers, making selection and shorting more fruitful.

- Higher cash yields: less drag from cash balances and collateral.

- Two-way markets: where some stocks fall even when the index is flat, creating opportunity on both sides.

That doesn’t guarantee successbut it helps explain why some institutional investors continue to allocate to equity long/short strategies, especially when they want a defensive tilt without going fully risk-off.

Practical Takeaways (Without the Sales Pitch)

If you’re evaluating why a long/short fund disappointed, the most common explanation isn’t “the manager forgot how to invest.” It’s usually a combination of:

- being partially hedged during a strong bull market,

- paying higher fees for complexity,

- absorbing shorting frictions and occasional squeezes,

- and operating in a market where correlations and momentum reduced the advantage of stock selection.

The best way to think about long/short funds is not “Will this beat the S&P 500 every year?”

A better question is: “What role does this play in my portfolio, and what kind of disappointment am I signing up for?”

Because yesthere will be disappointment. Investing is a disappointment delivery system with occasional fireworks.

Real-World Experiences and Lessons Learned (500+ Words)

Here are common experiences investors and advisors often report around long/short fundsthe kind of “I wish someone told me this sooner” insights that don’t always make it into glossy fact sheets.

No hero stories, no secret sauce, just what tends to happen in the wild.

1) “I bought it for protection… then it fell anyway.”

A frequent experience is buying a long/short fund right after a scary market momentsay, after a sharp correctionbecause it sounds safer than a regular stock fund.

Then the next drawdown arrives and the fund still loses money. Investors feel tricked, but the fund may have done exactly what it was designed to do:

lose less than a fully exposed equity fund, not avoid losses altogether.

The lesson: long/short funds are usually about risk shaping, not risk deletion. If you want something that aims to profit in a crash, you’re talking about a different toolkit (and usually different costs and trade-offs).

2) “It underperformed every year… so why did I own it?”

Many investors judge a long/short product against the S&P 500 because that’s the scoreboard they recognize. In long bull runs, that can look uglyyear after year.

The experience becomes a slow drip of regret: “I paid higher fees to lag the index.” That regret can be rational if the fund was purchased as a return engine.

The lesson: if the fund’s job is to lower volatility or reduce drawdowns, you need to measure it against the job description, not against a roaring bull market.

Otherwise, it’s like complaining your raincoat isn’t winning a beauty contest.

3) “I didn’t realize how much the short side can hurt in a melt-up.”

Investors often assume the short book is a neat hedge that politely offsets risk. In reality, the short book can be a persistent drag during powerful ralliesespecially when the market leadership is narrow and intense.

If the manager is short expensive, popular, momentum-driven names, the short book can feel like trying to stop a freight train with a strongly worded email.

The lesson: a short book is not just “insurance.” It’s an active set of bets with real risk, including squeeze risk and behavioral risk (your patience).

4) “I underestimated taxes and turnover.”

Long/short strategies can involve higher turnover. Turnover can mean more realized gains in taxable accounts, and short positions can create additional complexities.

The experience is frustrating: the pre-tax return looks mediocre, then the after-tax result looks worse.

The lesson: long/short funds are often better evaluated in the context of account type, holding period, and total after-fee, after-tax outcomesnot just the headline performance chart.

5) “The fund drifted from what I thought it was.”

Some investors buy “long/short” assuming it always means a stable, defensive profile. But manager behavior can change with opportunity:

net exposure might rise when the manager feels bullish, or the fund might hedge more aggressively when risk looks elevated.

The experience becomes: “Waitwhy does this feel like a regular stock fund now?” or “Why is it suddenly so cautious?”

The lesson: you have to track exposures (net and gross), not just labels. A long/short fund’s behavior can change materially without changing its name.

6) “I learned the hard way that ‘alternative’ doesn’t mean ‘better.’”

The most valuable experience many investors report is a mindset shift:

alternative strategies aren’t magical. They’re just different combinations of risks, costs, and expected outcomes.

Some will shine in certain environments and disappoint in others. The job is to understand the trade-offs and size the allocation accordingly.

The lesson: treat long/short as a tool, not a trophy. Small, purposeful allocations with realistic expectations tend to create better investor experiences than big, emotionally driven swings.

Conclusion

Long/short funds have often performed poorly because the real world is messy: bull markets punish partial hedges, shorting is expensive, correlations can swamp fundamentals, momentum can torch shorts, and fees raise the hurdle.

The strategy isn’t “broken”but it’s frequently misunderstood, mis-benchmarked, and misused.

If you’re going to use a long/short fund, make sure you’re buying what it can realistically deliver: a different ride, not a guaranteed better destination.

And if anyone promises “market-like returns with half the risk” with a straight face, politely check for hidden wires and a trap door.