Europe is packed with wildlife that doesn’t need a passport to be dramatic: owls that look like tiny philosophers,

foxes that treat city parks like their personal commute route, and underwater creatures that seem like they were

designed by a sci-fi director with a caffeine budget. Every year, the German Society for Nature Photography (GDT)

takes all that wild energy and funnels it into one of the most respected nature photo contests on the continent:

European Wildlife Photographer of the Year (often shortened to EWPY/EWPY-style naming in coverage). [1]

The point isn’t just “pretty animal, big lens.” The winners tend to land where story, craft,

and ethics overlapimages that are technically sharp, emotionally sharp, and captured with respect for living things.

For the 2025 edition, the overall winner was German photographer Luca Lorenz with “Silent Despair”,

a black-and-white moment featuring a pygmy owl and a quiet punch in the feelings. [2]

(Yes, wildlife photography can absolutely make you stare at a wall afterward. In a good way. Mostly.)

What Is the German Society for Nature Photography (GDT)?

GDT is a German association dedicated to nature photography and photographersthink community, standards, education,

exhibitions, and competitions. One of its flagship public contests is European Wildlife Photographer of the Year,

which is open to photographers living in Europe and also to GDT members (even if they live elsewhere). [1]

The contest has been running for over two decades, and GDT positions it as a showcase for how diverse and innovative

contemporary nature photography has become. [1]

If you’re the kind of person who reads contest deadlines like they’re concert tickets: the current call for entries

lists a closing date of March 1, 2026. [1]

How the Competition Works (Without the Boring Bits)

EWPY is structured around categories that cover both classic wildlife subjects and more conceptual nature imagery.

In the 2025 gallery presentation, GDT highlights categories including Birds, Mammals,

Other Animals (reptiles, amphibians, insects, invertebrates), Plants & Fungi,

Landscapes, Underwater World, Man and Nature, and Nature’s Studio

(more experimental, design-driven work), plus youth categories. [2]

There are also special honors, including the Fritz Pölking Prize (portfolio/storytelling work) and the

Rewilding Europe Award, which spotlights photography connected to rewilding and nature restoration. [2]

What “Best Wildlife Photos” Really Means Here

According to the competition’s own framing, judging is a balancing act: spectacular images are everywhere now, so the

jury looks for photographs that combine strong visual intent with compelling content and (often) a contemporary message.

They also emphasize originalityimages that don’t melt into the modern internet’s big soup of “same bird, same branch,

same blur.” [2]

In 2025, GDT reports that 1,120 photographers from 48 countries submitted

more than 24,500 images. [2] That’s not a competition; that’s an entire wildlife

streaming service.

Gallery Tour: 30 “Picture Lessons” Inspired by Europe’s Best Wildlife Photographs

Instead of trying to cram 30 captions into your eyeballs at once, let’s do something more useful:

30 picture lessonsthe kinds of scenes, ideas, and creative choices that show up again and again

among top-tier European wildlife photographs (including the 2025 winning set). [2]

Consider this a guided tour of what makes award-level nature photos feel like more than “nice wallpaper.”

-

Quiet drama beats loud chaos

The 2025 overall winner “Silent Despair” is proof that you don’t need explosionsjust emotion, restraint, and a

moment that says something about survival. [2] -

Birds aren’t just “birds”they’re behavior machines

The Birds category explicitly celebrates migration, feeding drama, unusual shapes, and elegance in flightso

behavior matters as much as feathers. [2] -

Tell the story with light, not text

A shaft of dawn light can do more narrative work than a paragraph. Judges consistently reward intentional light

that guides the viewer’s eye. [2] -

Use distance as an ethical tool (and a compositional tool)

Ethical practice and strong images often align: telephoto distance keeps animals behaving naturally, and it can

simplify backgrounds for cleaner frames. [3] -

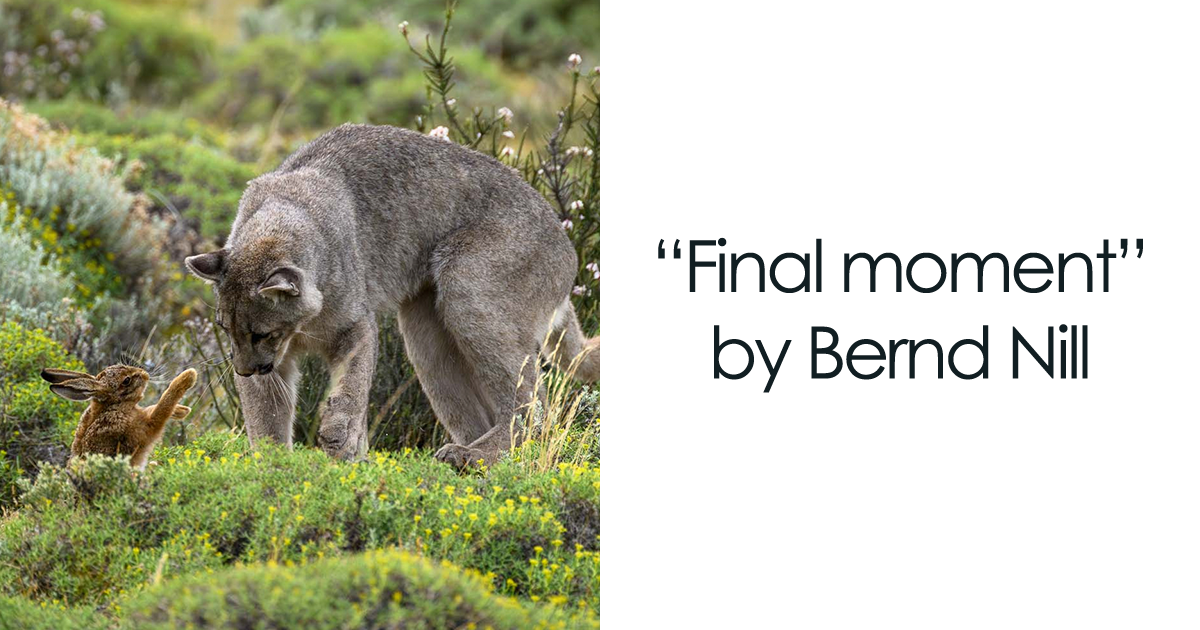

Mammals win when they feel like individuals

GDT’s Mammals category description highlights character, behavior, and habitatphotos that feel like

personality, not just “mammal sighting.” [2] -

Make “small” feel epic

In “Other Animals,” the stars are often insects, amphibians, and invertebratessubjects that become huge

when you use perspective, macro detail, and bold design. [2] -

Plants & fungi are the ultimate abstract artists

This category is basically an invitation to paint with light: textures, translucence, dew, and modern composition

are part of the brief. [2] -

Landscapes aren’t “empty”they’re habitats with stakes

The Landscapes category ranges from cultural landscapes to remote regions, including weather and the shaping power

of wind and waterhabitat is the headline. [2] -

Underwater images win by revealing a hidden world

The Underwater World category is explicitly about showing life in oceans, rivers, and lakesfreshwater and saltwater

mysteries included. [2] -

“Man and Nature” is where photography becomes a mirror

This category is for images that show human interferencethought-provoking, astonishing, or darkly funny

(because reality has jokes, apparently). [2] -

Nature’s Studio rewards experimentation

This category values colors, shapes, and interpretation beyond literal representationyour permission slip to get

weird in a sophisticated way. [2] -

Let the background do half the work

Clean backgroundssnowfields, fog, dark watercan turn a common species into a graphic icon. Isolation is a classic

technique in bird and wildlife shooting. [4] -

Action is great, but timing is greater

Burst mode is useful, but it’s not a substitute for anticipation. The best “action” frames still look deliberate

because the photographer predicted the peak moment. [4] -

Emotion is allowed (even in a science-y genre)

The strongest images often land because they feel like somethingtender, tense, uneasy, triumphantwithout turning

animals into cartoon characters. -

Go low for intimacy

Eye-level perspective makes wildlife feel like a subject, not a specimen. It also creates stronger separation and

more immersive depth. -

Use weather as a co-author

Snow, rain, heat haze, and coastal wind aren’t “bad conditions”they’re mood engines. Landscapes, birds, and mammals

can all gain story from weather. [2] -

Show the “edge” habitats

Europe’s wildlife often thrives at borders: forest meets farmland, city meets river, road meets meadow. Those edges

naturally create tension and narrative. -

Let conservation be present without turning into a poster

Powerful images can raise awareness without shouting. GDT’s own framing connects winning photography to emotional

impact and conservation awareness. [2] -

Don’t chase; compose

Ethical guidance from major conservation organizations emphasizes: don’t harass wildlife, don’t alter habitat,

and back off if the animal shows stress. [5] -

Respect nesting and denning behavior

Ethical bird photography guidance warns against pressuring nesting birds and sensitive areasspace protects wildlife

and protects the story you’re trying to tell. [6] -

Use “negative space” like it’s a design degree

Minimalism turns wildlife into symbolism. A small subject in a big frame can suggest vulnerability, solitude,

or scale in a single glance. -

Try monochrome when color distracts

Black-and-white can strip a scene to structure, gesture, and emotionone reason it can feel timeless in contests.

(The 2025 overall winner is a strong example.) [2] -

Let “ordinary” species be extraordinary

The most memorable images aren’t always rare animals. A common bird in uncommon light can beat a “rare sighting”

shot that’s visually messy. -

Use a long lens to protect behavior

Telephoto technique is often recommended for birding and wildlife because it keeps your distance while still filling

the frameless disturbance, more authentic behavior. [4] -

Underwater: simplify the chaos

Underwater scenes can get visually noisy fast. Winning images often rely on strong subject separation, clean light,

and clear story cuespredator/prey, symbiosis, or habitat. -

“Man and Nature” works best when it’s specific

Instead of generic “humans are bad” vibes, the strongest images show a concrete interaction: barriers, light

pollution, bycatch, habitat fragmentation, or resilience. -

Portfolios win with cohesion

The Fritz Pölking Prize is built around story/portfolio workimages that hold together as a narrative, not just

a single lucky frame. [2] -

Youth categories prove the secret ingredient is attention

GDT’s youth entries don’t have to match the main category themesyoung photographers can submit their best images,

period. The message: curiosity and focus beat fancy excuses. [2] -

Great wildlife photography is part science, part art

Serious wildlife images require understanding behavior, patience, and craftthe “science and art” blend is a recurring

theme in how major outlets discuss wildlife photo competitions. [7]

How to Use These 30 Pics as a Skill Upgrade (Not Just a Scroll)

1) Steal the structure, not the subject

You don’t need the exact owl, the exact fjord, or the exact fog machine the universe provided that one photographer at

precisely 6:12 a.m. What you can copy ethically is the structure: minimalism, layered habitat, behavior timing, or a

strong color story.

2) Build an “ethics checklist” you actually follow

The best wildlife photos tend to come from photographers who treat ethics as part of technique. Practical guidance from

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and major conservation voices emphasizes giving animals space, avoiding disturbance, and

prioritizing welfare over the image. [5] If you want a simple rule: if the animal changes behavior because of you,

the photo is already too expensive.

3) Use real distance rules when you have them

In many protected areas, “reasonable distance” isn’t a vibeit’s a regulation. For example, a U.S. National Park Service

safety page notes a minimum distance requirement of 50 yards from park wildlife in that park’s guidance. [8]

Even if you’re shooting in Europe, the principle transfers: rules exist because wildlife doesn’t get a second chance at calm.

4) Shoot for a message, not just a moment

Contest juries increasingly reward images that say something contemporaryhabitat pressure, coexistence, resilience

without turning the animal into a prop. GDT’s own jury commentary reflects that push toward fresh vision and meaningful content. [2]

Experience: What It Feels Like to Chase a Europe-Worthy Wildlife Photo (500+ Words)

The first thing you noticeif you ever try to “shoot like a contest winner”is how much of the experience happens

before you touch the shutter. You’re not collecting animals like trading cards; you’re collecting tiny clues:

a shift in wind, a change in posture, the way birds look around before they launch, the way a mammal freezes when it

thinks it heard something. Wildlife photography is basically an advanced class in paying attention… taught by professors

who refuse to email you the syllabus.

Then comes the waiting, which sounds boring until you realize waiting is where the story shows up. At first you tell

yourself, “I’m waiting for the animal.” But after a while you understand you’re also waiting for the scene to make

sense. The light settles. The background becomes quieter. The animal stops being “a subject” and starts being a

character in a place that feels real. That’s when images begin to look less like sightings and more like moments.

The ethical part isn’t a separate lecture you sit throughit’s baked into the experience. Keeping distance isn’t just

“being nice”; it changes your photography. When you’re not crowding wildlife, you start using framing instead of pressure.

You begin to appreciate negative space, weather, and habitat as storytelling tools. You learn that a long lens isn’t a

brag; it’s a boundary. And you get better at reading “no,” because animals say it constantlyby turning away, pausing,

flattening posture, calling out, or simply leaving. Respecting that “no” is the difference between a photo you’re proud

of and a photo you’re trying to justify.

There’s also a humbling moment when you realize the best shots often feel quiet. The internet trains us to chase

spectaclefangs, talons, explosions of action. But the images that stick (like GDT’s 2025 overall winner) are often about

mood: a still bird in a wide frame, a mammal in soft fog, an underwater creature drifting through a clean slice of light.

The drama isn’t created by the photographer. It’s revealed by patience.

And yes, your memory card will include a lot of “almost.” Almost sharp. Almost perfectly timed. Almost the right wing

position. That’s not failure; that’s the process. Contest-level wildlife photography is built on the unglamorous

repetition of returning to places, learning patterns, and showing up when nothing is guaranteed. It’s a practice in

humility with occasional rewardslike a bird lifting its head at exactly the right second, or a fox pausing on the edge

of a field as the sky turns into a watercolor.

The weirdest part? Even when you don’t get the photo, you often leave with something better: a deeper understanding of

how wild lives work. You notice relationshipspredator and prey, parent and young, animal and habitat, nature and human

footprint. Those relationships are what top competitions quietly celebrate. The “best wildlife photographs in Europe”

aren’t just pretty pictures; they’re tiny, persuasive arguments for paying attention to the living worldbefore it

changes, or disappears, or both.