“Carbon transformation” sounds like something a superhero does in a lab accident. In investing, it’s less cape-and-cowl and more

spreadsheets-and-capex: the slow, messy, enormously expensive (and occasionally profitable) process of rewiring how the global economy

makes energy, moves stuff, manufactures materials, and heats buildingswhile trying to emit a whole lot less carbon along the way.

That’s the big idea behind the Talk Your Book episode featured on A Wealth of Common Sense, where the conversation

zooms in on a simple but underrated angle: the next wave of climate “winners” won’t just be the obvious clean-tech darlings. A large

chunk of the opportunity may come from high-emitting industries that successfully reinvent themselvesplus the companies that sell them

the tools to do it.

What “carbon transformation” actually means (and why it’s not just “buy solar”)

The internet loves tidy labels: “green good, fossil bad.” Real-world decarbonization is more like renovating a house while you’re still

living in itwhile your kids are yelling, the dog ate the contractor’s invoice, and the electricity has to stay on. Energy systems are

huge, long-lived, and deeply entangled with politics, supply chains, and daily life.

Carbon transformation investing is essentially a bet on transition:

companies (often in heavy-emitting sectors) that are committing real money, real projects, and real operational changes to cut emissions,

improve efficiency, and shift their product mixideally without blowing up profitability.

Two flavors of opportunity

-

“Pure-play” solutions: renewable power, grid hardware, batteries, EV supply chains, energy efficiency, electrification,

clean fuels, and software that squeezes waste out of industrial processes. -

“Brown-to-green” transitions: utilities retiring coal and building wind/solar/storage, industrials decarbonizing heat,

materials firms lowering clinker in cement, transport companies electrifying fleets, and oil-and-gas players leaning into methane

abatement, carbon capture, and lower-carbon molecules (with all the caveats that come with that).

Why investors keep running into this theme (even if they didn’t mean to)

Start with the awkward truth: global energy use is still massive, and forecasts that assume “no big policy/technology surprises” often

project a lot more energy demand in the future. In the U.S. EIA’s International Energy Outlook reference case, world energy consumption

rises by nearly 50% by 2050. More people + more economic activity + more electrification + more data centers = bigger appetite.

Then add the not-so-cute part: atmospheric CO₂ keeps climbing. You don’t need to be a climate modeler to understand that “more CO₂” is not

a loyalty program you want to max out. The investment implication is straightforward: whether progress is fast or slow, the economy is

under pressurepolicy pressure, investor pressure, consumer pressure, and physics pressureto emit less per unit of output.

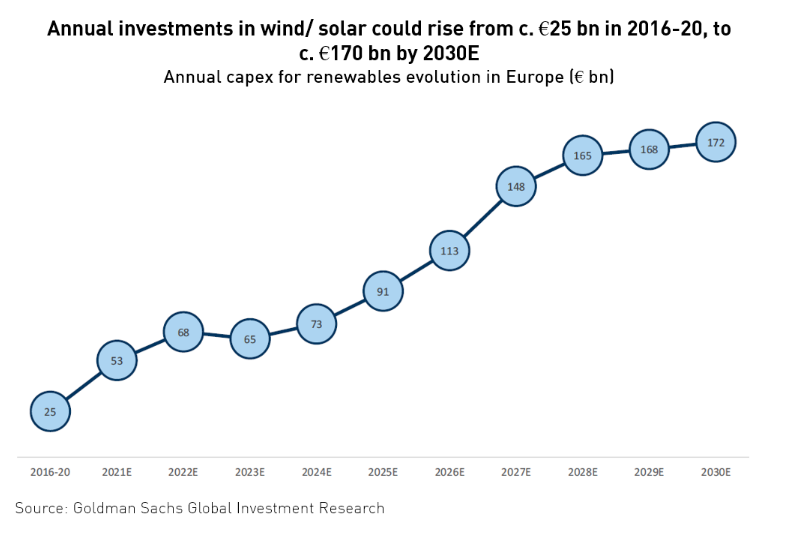

Finally, there’s the money. Serious decarbonization isn’t a vibes-based initiative; it’s a physical rebuild of assetspower plants, grids,

factories, vehicles, buildings, and fuel infrastructure. Some scenarios estimate trillions of dollars per year in incremental investment

over decades. Translation: this is a multi-cycle capex story, not a one-year fad.

The “Talk Your Book” lens: invest in the transition, not the Instagram

The episode that inspired this headline featured Roger Mortimer (KraneShares) discussing a “carbon transformation” approachlooking for

companies in traditionally high-emitting industries that are taking credible steps toward decarbonization, plus enablers in the value

chain. The point wasn’t “every green thing goes up forever.” It was: where are the durable cash flows and the realistic pathways

to lower emissions?

Key takeaways investors can steal (politely) from the conversation

-

Energy transition ≠ energy replacement overnight. The market tends to price in either a miraculous overnight switch or

total failure. Reality usually lives in the boring middle. -

Look for proof, not press releases. Targets matter less than actions: capital spending plans, contracted projects,

operational metrics, and repeatable economics. -

Winners can come from “ugly” sectors. Utilities, industrials, materials, and transportation don’t sound sexyuntil you

realize decarbonizing them is the whole game. -

ESG labels don’t automatically reduce emissions. “ESG” can mean risk management, values alignment, exclusion screens,

or impact goals. Investors should know which game they’re playing.

Where the carbon transformation is happening (with specific examples)

1) Electricity: the grid is the foundation of everything else

Electrification is the climate equivalent of “turn it off and back on again.” But it only works if the electricity gets cleaner and the

grid can handle new loads (EV charging, heat pumps, industrial electrification, and that one neighbor who mined crypto for a month and

won’t stop talking about it).

- Utilities retiring coal units, expanding wind/solar, adding storage, and modernizing transmission.

- Grid equipment makers: transformers, switchgear, power electronics, advanced conductors, and control software.

-

Solar economics have improved dramatically over time; cost declines are one reason adoption keeps compounding, even when

headlines get dramatic.

2) Transportation: electrification, efficiency, and the hard-to-electrify problem

Passenger EVs get most of the attention, but “transportation” is also trucks, ships, aviation, rail, and last-mile delivery fleets. The

transition won’t be one-size-fits-all:

- Light-duty vehicles: batteries + charging networks + grid upgrades + better manufacturing.

- Heavy-duty trucking: battery-electric in many short/medium routes; hydrogen and other fuels may compete on long-haul.

- Aviation: sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) looks like a pragmatic near-term lever, alongside efficiency upgrades.

- Shipping: efficiency, alternative fuels (like green methanol or ammonia), and port infrastructure.

3) Heavy industry: the “hard part” that can’t be solved with a cute app

Steel, cement, chemicals, and refining are high-emitting because physics and chemistry are involved, not because they forgot to recycle.

Cutting industrial emissions often means some mix of electrification, green hydrogen, alternative feedstocks, carbon capture, and process

redesign.

- Steel: more recycling via electric arc furnaces; potentially hydrogen-based direct reduced iron for primary steel.

- Cement: lower-clinker blends, alternative fuels, carbon capture, and novel cements in some applications.

- Chemicals: electrified cracking, green hydrogen, and circular feedstocks.

4) Buildings: efficiency is the unsexy compounder

If you want a climate solution that tends to pay you back in energy savings, buildings are it: insulation, heat pumps, efficient HVAC,

smart controls, and better materials. Not glamorous, but so is brushing your teethyet here we are.

Policy is a feature, not a bug (but it can change the rules mid-game)

Decarbonization is heavily influenced by incentives, standards, and disclosure regimes. In the U.S., clean energy tax credits and

industrial incentives have been central to project economics for hydrogen, carbon capture, renewables, and manufacturing. Guidance and

final rules matter because they determine what actually qualifies in practice.

Three policy realities investors should price in

- Implementation risk: it’s not enough to have a law; details, timelines, and enforcement drive real-world outcomes.

- Political risk: incentives can be extended, tightened, phased out, or restructured.

- Compliance and measurement: emissions accounting, verification, and reporting are increasingly important.

For example, clean hydrogen and carbon capture policies can hinge on lifecycle emissions measurement, credit eligibility, and verification

frameworks. Even small regulatory changes can swing project returns from “bankable” to “nice PowerPoint, though.”

Carbon markets vs. carbon transformation: cousins, not twins

A common confusion: “carbon investing” can mean buying carbon allowances/credits (exposure to carbon prices), or it can

mean buying companies that will benefit from decarbonization. They are related, but behave differently.

Carbon allowance exposure

Compliance markets (like certain cap-and-trade programs) create tradable allowances with rules about coverage, caps, and auctions. These

markets can be volatile, political, and policy-sensitive. They can also be powerful incentives for emissions reductions when designed

well. For investors, they’re closer to a commodity-like exposure than an operating business.

Carbon transformation equity exposure

This is about business models: margins, competition, supply chains, and technology curves. The upside can be larger if a company

reinvents itself and gets re-valued. The downside is also real: transitions are expensive, execution is hard, and markets rarely reward

“trying really hard” without results.

How to evaluate “transition” companies without getting hypnotized by buzzwords

1) Follow the money: capex and contracts

Net-zero targets are cheap; steel mills are not. Look for capital allocation you can measure: announced projects with financing,

long-term offtake agreements, procurement commitments, and milestones hit on schedule.

2) Look for unit economics that improve over time

Technology often gets cheaper with scale and learning curves. Solar is the classic example, with substantial cost declines over the past

decade-plus. When unit costs fall and reliability improves, adoption tends to stick.

3) Watch for “transition moats”

In a transition, moats often come from manufacturing know-how, permitting expertise, integration skills, access to critical materials,

superior grid interconnections, or customer relationships. In other words: boring advantages that make accountants smile.

4) Don’t ignore the balance sheet

Transitions can be capital-intensive. If a company is funding a decarbonization plan with a shaky balance sheet, you may be buying a

great idea attached to a refinance risk.

ESG reality check: disclosure is evolving, and “impact” is tricky

“ESG” gets treated like a single product. It isn’t. It can mean:

(a) excluding certain industries, (b) tilting toward lower emissions, (c) engaging with companies to improve practices,

or (d) targeting measurable outcomes.

The practical investor takeaway: be specific about your objective. Are you trying to reduce portfolio risk? Align with values? Influence

corporate behavior? Capture a theme? Different goal, different tool.

Disclosure rules and reporting expectations have also been in flux in the U.S., which matters because investors can’t price what they

can’t see. Regardless of where regulation lands, many large companies and asset managers have continued building climate reporting

systemsbecause global capital markets increasingly expect it.

Risks that deserve more airtime than the “to the moon” threads

- Valuation risk: thematic trades can get expensive fast. Paying any price for “the future” is still paying any price.

- Policy whiplash: subsidies, credits, and standards can changeand projects can stall when the math shifts.

- Technology risk: some solutions scale beautifully; others remain niche or get leapfrogged.

- Commodity and supply-chain risk: materials, rare earths, grid components, and manufacturing bottlenecks can change costs.

- Greenwashing risk: some companies market “transition” harder than they execute it. Proof matters.

Putting it into a portfolio: common-sense approaches (not a one-stock sermon)

Carbon transformation investing isn’t an all-or-nothing bet. Most investors implement it as a sleeve within a diversified portfolio,

often with a mix of:

- Broad market exposure (because the future still includes boring companies that sell toothpaste).

- Targeted transition themes (clean power, electrification, efficiency, industrial decarbonization).

- Quality filters (balance sheet strength, profitability, and disciplined valuations).

- Selective “brown-to-green” exposure (companies with credible plans and measurable progress, not just slogans).

The most underrated “strategy” is also the least fun: position sizing. Even if you love the theme, treat it like a themesize it so you

can hold through volatility without rage-selling at the exact wrong time.

The bottom line

The carbon transformation is not a straight line, and it’s not a single sector. It’s a multi-decade remodeling of the physical economy.

The Talk Your Book framing is useful because it pushes investors away from the simplistic “clean vs. dirty” narrative and toward a

more practical question: who is actually transformingand who is enabling the transformation?

Some of the best opportunities may come from unexpected places: heavy industry, grid infrastructure, efficiency, and the quiet companies

that make the hardware and software powering the transition. The trick is to separate durable transformation from fashionable marketing,

and to remember that long-term themes still have short-term drawdowns.

Experience Section: 5 “Field Notes” Investors Often Live Through (Composite Stories)

You asked for experiencesso here are five realistic, composite investor “field notes” that reflect patterns people commonly encounter

when they start thinking about investing in the carbon transformation. These aren’t personal anecdotes or promises of results; think of

them as a map of emotional potholes and practical lessons.

1) The “I bought clean energy… and then oil ripped” moment

A classic experience: an investor allocates to clean energy right as traditional energy rallies. Suddenly, the portfolio feels like a

morality play written by the market: “You chose virtue; here’s your underperformance.” The lesson is that energy transitions can happen

alongside fossil fuel demand, not instead of itespecially when global energy consumption is growing and supply constraints appear.

Investors who survive this phase usually reframe the theme as a long-duration transformation story, not a quarterly scoreboard.

2) The “policy headline whiplash” phase

This one feels like watching a tennis match played by lawmakers. A new incentive sparks optimism, then a court case or guidance update

spooks the market, then a revision arrives with different rules. Investors often learnsometimes the hard waythat policy is embedded in

project economics. The people who keep their sanity tend to diversify across sub-themes (grid, efficiency, industrial tech) rather than

betting everything on one subsidy-dependent corner.

3) The “my favorite technology isn’t scaling as fast as the PowerPoint said” reality check

Early-stage decarbonization technologies can be incredible and still struggle: supply chains, permitting, cost overruns, financing, and

customer adoption don’t obey your spreadsheet. Investors who adapt usually shift from “cool tech” to “repeatable unit economics” and

“proven deployment.” They may keep a small venture-like sleeve for moonshots while anchoring the theme in mature, cash-generating

businesses.

4) The “transition company” that looks messy until it suddenly doesn’t

This is the carbon transformation sweet spotwhen it works. The company isn’t a pure-play clean-tech name; it’s a familiar industrial,

utility, or manufacturer with heavy emissions and a very unglamorous product. Progress looks slow: capex rises, margins wobble, analysts

argue. Then the company starts hitting milestonesnew facilities come online, efficiency improves, customers sign longer contracts, and

the market begins treating it less like a legacy business and more like a transition leader. The key experience here is patience:

transformation is often invisible right up until it becomes obvious.

5) The “I realized this is a portfolio construction problem, not a prediction contest” breakthrough

Many investors begin with a single question: “Which technology wins?” Over time, a more useful question emerges: “How do I build a

resilient allocation that benefits from the transition across multiple pathways?” That often leads to a blend of exposures:

electrification and efficiency (the steady compounders), grid and power infrastructure (the picks-and-shovels), and selective industrial

decarbonization (the transition candidates). The investor experience shifts from adrenaline to processless “talk your book,” more “run

your plan.”

If there’s a unifying takeaway from these experiences, it’s this: the carbon transformation is a long game with loud headlines.

Investors who approach it with humility, diversification, and realistic time horizons tend to stay in the arena long enough to benefit

from the compounding. Investors who treat it like a meme trade tend to get… educational outcomes.