Building a calculator in C++ is like making a grilled cheese: it seems “too basic” until you realize it teaches you

everything that mattersheat (logic), timing (control flow), and not burning the whole kitchen down (input validation).

In one small project, you’ll practice variables, functions, switch-case,

loops, and safe input/output. And the best part? You end up with a program you can actually run,

show off, and upgrade.

This guide walks you through how to create a calculator in C++ in four clean steps, using standard C++ tools

(no fancy frameworks, no mysterious libraries, no “just copy this 400-line file and trust me” energy). We’ll build a simple

interactive calculator that supports addition, subtraction, multiplication, and divisionplus basic error handling for

bad input and division by zero.

What You’ll Build

- A console-based C++ calculator that runs in a loop until the user quits

- Support for +, –, *, and /

- Safe numeric input (handles letters, junk input, and accidental keyboard mashing)

- Division-by-zero protection (because math is picky like that)

- Nicely formatted output for a better user experience

Step 1: Define the Calculator’s Rules (Before You Write Code)

Pick your “calculator scope”

A calculator can be as small as “two numbers and an operator” or as big as a full expression parser

(like typing 12 + 3 * (7 - 2)). For this tutorial, we’ll keep it beginner-friendly and practical:

- User enters a number

- User enters an operator (+, -, *, /)

- User enters another number

- Program prints the result

- Repeat until the user chooses to quit

Choose numeric types wisely (aka: avoid “Why is 5/2 = 2?”)

If you use int, division will perform integer division (so 5 / 2 becomes 2).

That’s correct in “integer math land,” but it surprises humans. For a general-purpose calculator, use double.

You’ll get results like 2.5, which is what most people expect.

Set up your project essentials

You’ll typically need:

<iostream>for input/output<iomanip>for formatting (like decimal precision)<limits>for robust input cleanup

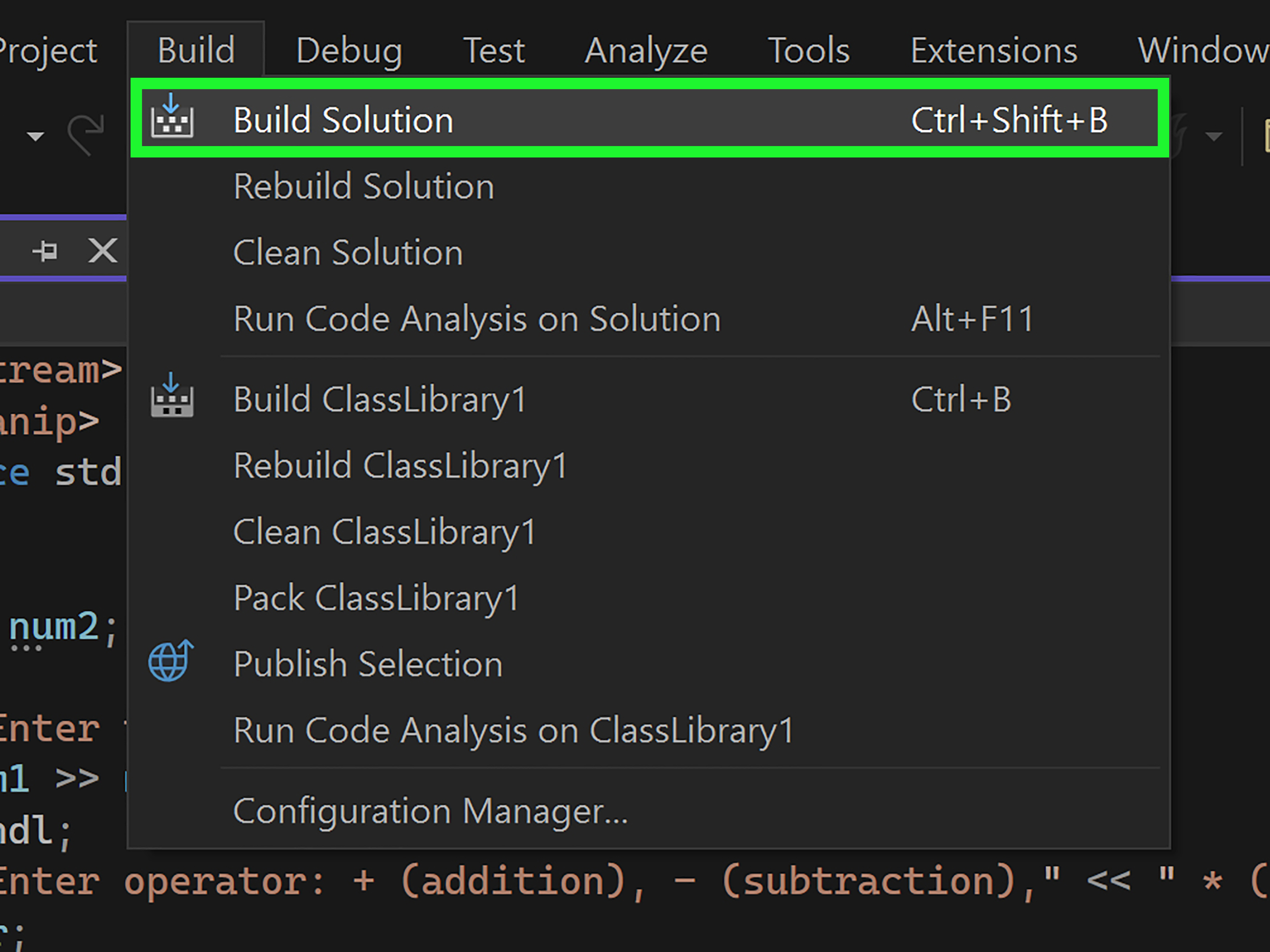

By the end, your code will be easy to compile in any standard C++ environment:

Visual Studio (Windows), clang++ (macOS), or g++ (Linux).

Step 2: Build the “Brain” (A Calculate Function + switch-case)

Why a function?

You could cram all the logic into main(), but that’s how tiny programs become spaghetti fast.

A dedicated function keeps your calculator readable and testable:

- Input layer: gather numbers/operator safely

- Logic layer: compute the result

- Output layer: display the result cleanly

Use switch-case for operators

A switch statement is a natural fit when you’re choosing behavior based on a single valuelike an operator.

We’ll switch on a char such as '+' or '/'.

Notice the bool& ok reference parameter. That lets the function report “success vs. failure”

without throwing exceptions or printing inside the logic layer. It’s a clean separation:

the brain computes, the UI talks to the user.

Step 3: Add Input Validation (Because Users Are Chaos)

The real enemy: invalid input

The #1 way beginner console programs break is input handling. If a user types pizza when you expect a number,

std::cin enters a failed state and future reads may stop working until you reset it.

The fix is simple and standard:

- Check if extraction (

>>) succeeded - If it failed: clear the error flags and discard the bad input line

Read the operator safely

Operators are single characters, so we can read a char and confirm it’s one of the supported options.

We’ll also support q to quit.

Run the calculator in a loop

Now we combine everything:

- Read first number

- Read operator

- If quit, stop

- Read second number

- Compute + show result (or show an error message)

Step 4: Polish Output, Test Edge Cases, and Upgrade

Make output readable

If you’re using double, results can show a lot of decimals. That’s fine for science,

but most humans prefer a tidy look. Use <iomanip>:

That gives you consistent, user-friendly output like 12.50 instead of 12.5.

Test the “gotchas”

- Division by zero: 10 / 0 should show an error, not crash

- Invalid operator: should re-prompt

- Non-numeric input: should re-prompt (and not get stuck)

- Integer-looking inputs: 5 / 2 should print 2.50 if you format to two decimals

Easy upgrades (once the basics work)

- Add more operators:

%(integers only), power, square root - Store a running total (“memory” buttons like M+, MR)

- Turn it into a “desk calculator” that accepts full expressions

- Add unit tests (even simple ones) to verify correctness automatically

Full Working Example: Simple Interactive C++ Calculator

Here’s a complete program you can copy, compile, and run. It follows the same four-step structure:

input helpers, calculation function, loop, and nice output formatting.

Troubleshooting Cheatsheet

-

My program keeps repeating the same error message.

You probably didn’t clear the stream state and discard the bad input line. Use

cin.clear()andcin.ignore(...). -

My switch runs the wrong case.

Missingbreakcan cause “fall-through.” Each case should end with abreak

unless you intentionally want multiple cases to share logic. -

5 / 2 prints 2 instead of 2.50.

Usedouble(notint) and format withfixed+setprecision. -

My operator input reads weird characters.

Be careful mixinggetlinewithcin >>. This program uses extraction consistently,

which avoids most whitespace issues.

Experiences: What Building a C++ Calculator Teaches You (and How It Usually Goes)

If you’ve never built a calculator in C++ before, the early experience is often a mix of confidence and confusion:

confidence because the math is simple, confusion because the computer is extremely literal. Most learners start by

writing something like “read two numbers, ask for an operator, print the result,” and it works perfectly… right up until

someone (or you, five minutes later) types something unexpected.

One of the most common “aha” moments is realizing that input handling is part of the problem, not a side quest.

In real programs, users don’t behave like polite robots. They paste text, hit Enter too soon, type commas instead of dots,

or decide that the letter “e” should count as a number because it does in science class. When std::cin encounters

invalid input, it can enter an error state and keep refusing to read anything else until you clear it. That’s why using

cin.clear() and cin.ignore(...) isn’t “extra”it’s the difference between a calculator that feels solid

and one that feels haunted.

Another classic experience: the switch-case break trap. You write a clean switch, hit run, and suddenly the

calculator prints the wrong result (or multiple results). Nine times out of ten, it’s because you forgot break.

C++ will happily continue into the next case if you let it. Once you see it happen, you remember it foreverlike touching

a hot pan once and instantly becoming a lifelong oven-mitt enthusiast.

Then there’s the “why is division rude?” chapter. If you start with int, you discover integer division (5/2 = 2).

If you switch to double, you discover floating-point formatting (why so many decimals?). And if you try dividing by

zero, you learn the valuable life lesson that math has rules and computers enforce them with the emotional sensitivity of a

parking ticket. Handling division by zero becomes your first taste of defensive programming: checking conditions

before doing something risky, and responding with a helpful message instead of letting the program misbehave.

A subtle but satisfying experience is when you begin refactoring. At first, everything lives in main().

Then you split out readNumber(), and suddenly the loop looks cleaner. You add calculate(), and now the

logic is testable. You start seeing your program in layers: input, processing, output. That’s not just “good style”it’s a

foundational habit for bigger projects. Even if you never build a massive app, learning to break a problem into functions

makes you faster and more confident.

Finally, once the simple calculator works, the upgrade ideas show up naturally. People often want to accept full expressions,

add parentheses, or support multiple operations in one line. That’s when you realize you’ve been standing at the edge of

deeper topics: tokenizing input, operator precedence, parsing, and maybe even building a tiny interpreter. Your “toy”

calculator quietly becomes a gateway project. The experience is basically: you came for + and -,

but you leave knowing a lot more about how programs thinkand how to make them behave when humans don’t.

Conclusion

To create a calculator in C++, you don’t need a mountain of codeyou need a smart structure. Start with a clear scope,

implement the calculation logic with a switch-case, protect your program with input validation, and polish the output so it

feels professional. Once you have a working loop-based calculator, you can expand it into memory functions, new operators,

or even a full expression parser. Small project, big skills.