Mars has a reputation problem. It’s the dusty, cold neighbor that looks like it forgot to finish decoratingand then

set its thermostat to “eternal brisk.” But here’s the twist: if you squint past the doom-and-gloom headlines and

think like an engineer (or a very determined camping enthusiast), you start to notice something exciting.

The Red Planet is not a barren void. It’s a warehouse.

Not a warehouse full of ready-to-assemble IKEA apartments (tragically), but one stocked with the raw ingredients

humans need to survive: air molecules we can process into oxygen, water locked up as ice, dirt we can turn into

building materials, and enough sunlight to power a small city if we’re smart about it. The trick is that Mars rarely

hands you anything in a neat, labeled box. It hands you elements and compounds and says, “Good luck, science wizard.”

This is where the concept of living off the land gets upgraded from “foraging for berries” to

in-situ resource utilizationISRU for short. The big idea is simple: don’t bring everything from Earth.

Bring the tools to make what you need from what’s already on Mars. And the more we learn, the more it looks like

Mars has almost everything we need to build a livable footholdif we’re willing to do the work.

Mars Living 101: The “Make It There” Strategy (ISRU)

When people say “Almost everything we need to live on Mars is already there,” they’re not claiming you can step off a

spaceship and immediately grill hamburgers under a cozy Martian sunset. They mean the planet contains the basic

inputs: carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, minerals, and waterplus energy sources. What we’re missing is the easy

part: Earth’s friendly atmosphere, warm temperatures, thick radiation shielding, and “free” biology (like soil that

doesn’t try to poison your lettuce).

ISRU flips the mission plan. Instead of launching massive quantities of oxygen, fuel, water, and construction material,

you launch equipment that can extract and manufacture them. That cuts down payload weight (a huge deal when launching from Earth)

and supports long-term settlement rather than a short visit-and-wave mission.

The Mars checklist we’re trying to satisfy

- Breathable air (oxygen production and safe habitat atmosphere)

- Water (drinking, hygiene, agriculture, and making propellant)

- Food (reliable calories and nutrients, year-round)

- Shelter (pressure, insulation, radiation protection)

- Power (solar, nuclear, and storage)

- Fuel (especially for return trips and surface mobility)

- Health protection (radiation, dust, low gravity issues)

Now let’s look at the surprising part: Mars can contribute significantly to most of these categories.

Air: Mars Has PlentyJust Not the Kind You’d Like

Mars’ atmosphere is thin, cold, and mostly carbon dioxide. That sounds like a dealbreaker until you realize CO2

is a resource, not just a problem. Carbon dioxide contains oxygen. If you can split it efficiently, you can make

breathable oxygenand oxidizer for rocket fuel.

MOXIE proved the concept: oxygen from Mars air

NASA tested this idea on Mars with an instrument called MOXIE (Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment)

on the Perseverance rover. MOXIE demonstrated that you can pull in Martian air and produce oxygen using solid oxide electrolysis.

Over its mission, it generated a total of 122 grams of oxygen and hit a production rate as high as

12 grams per hour at high puritysmall-scale, but a real proof that “oxygen factories” are more than science fiction.

To be clear: MOXIE didn’t solve “how to supply a whole base.” It solved something just as important“is this physically

workable on Mars in real conditions?” That’s the difference between a great idea and a great idea that survives dust,

temperature swings, and the general Mars vibe of “your machinery looks tasty.”

Fuel is also hiding in plain sight

If you can make oxygen, you’re already halfway to rocket propellant. The other half is typically fuel like methane.

Methane can be produced using the Sabatier reaction: combine CO2 (from Mars air) with hydrogen

(from water) to make methane and water. You recycle the water, keep the methane, and suddenly the planet is helping you

gas up for the trip home.

In other words: Mars is basically a giant chemical pantry. You still need the appliances, though. And by “appliances,”

we mean industrial reactors, compressors, heat exchangers, and a power system that doesn’t faint when someone plugs in a kettle.

Water: Not Flowing Rivers, but a Very Promising Ice Bank

Water is the superstar resource for Mars living. It’s life support, agriculture support, and fuel support.

The good news: Mars has lots of water as ice. The better news: in some regions, it may be shallow enough to reach without

building a mining operation that looks like it belongs in a dystopian movie.

Where is the ice?

Mars has polar ice caps, but living right at the poles isn’t everyone’s dream neighborhood (especially for sunlight).

What’s exciting is evidence for subsurface ice in mid-latitudesareas that could balance workable temperatures, decent solar power,

and accessible water. Mapping projects have aimed to identify where ice is likely to be close to the surface, which helps planners

think like settlers, not just visitors.

If you can extract ice and melt it, you get:

- Drinking water (after purification)

- Oxygen (via electrolysis)

- Hydrogen (also via electrolysis, for methane production)

- Radiation shielding (water is excellent at stopping some radiation)

Water is heavy to launch from Earth, so local supply changes everything. It’s one of the strongest arguments that Mars settlement

might be more than a flag-and-footprints concept.

Food: Mars Doesn’t Have “Soil,” It Has “Regolith”… and Attitude

Here’s where Mars gets less generous. You can’t just plant seeds in the ground and expect a quaint little Martian farmers market.

The surface material is called regolith, and it’s not soil in the Earth sense. It lacks organic matter,

behaves differently, and may contain compounds that are problematic for humans and plants.

The perchlorate problem (aka “why your salad needs a hazmat plan”)

Mars regolith can contain perchlorates, chlorine-based compounds that are toxic at certain levels.

That doesn’t mean agriculture is impossibleit means it needs careful engineering. Strategies include:

- Hydroponics or aeroponics (growing without soil)

- Imported or manufactured growth media (treated regolith or engineered substrate)

- Bioremediation (microbes that can process harmful compounds)

- Closed-loop nutrient systems (recycling waste into fertilizer safely)

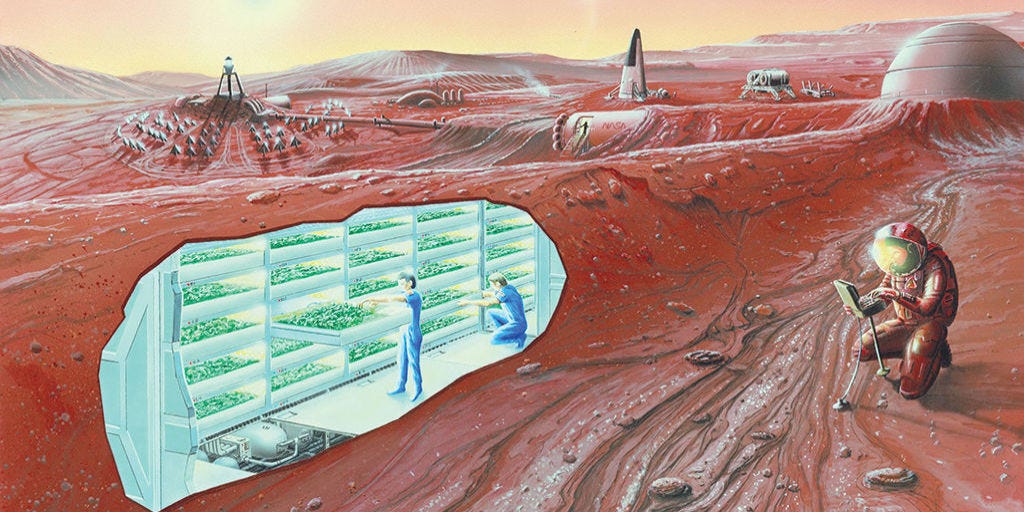

Many Mars food concepts focus on controlled environment agriculture: sealed greenhouses, LED lighting, tight humidity control,

and relentless monitoringmore “space lab” than “country garden.” But the goal is realistic: grow calorie-dense crops (potatoes,

wheat, legumes), leafy greens for vitamins, and maybe algae or fungi for efficient protein.

The optimistic takeaway is this: Mars supplies water and minerals; humans supply biology and control systems.

You’re not farming Mars. You’re farming on Mars.

Shelter: Mars Dirt Might Be Your Best Building Material

A Mars habitat has to do several jobs at once:

keep pressure in, keep radiation out, manage temperature swings, and resist dust storms that can sandblast equipment like a gritty car wash.

Shipping building materials from Earth would be expensive and limiting. So the obvious candidate is right under your boots: regolith.

How do you build with regolith?

Researchers and space agencies have explored multiple approaches:

- 3D printing using regolith-based “concrete” or binders

- Compressed blocks or sintered bricks (heating particles until they fuse)

- Regolith bags or berms piled over habitats for shielding

- Landing pad construction to prevent rocket exhaust from launching debris everywhere

The simplest early strategy might be the least glamorous: land an inflatable or rigid habitat, then bury it under a thick layer of regolith.

Think of it as a cozy bunker, except you’re doing it because cosmic rays are rude houseguests.

Longer term, building with local materials could create safer, roomier structures: tunnels, domes, storage vaults, and industrial spaces.

“Mars architecture” will likely look less like sci-fi glass bubbles and more like practical, shielded shapes designed for survival.

(Sorry, Instagram.)

Power: Mars Has SunlightBut You’ll Want Backup

Mars receives less sunlight than Earth, but there’s still plenty for solar powerespecially if you use efficient panels,

smart positioning, and energy storage. The challenge is that Mars also has dust: dust storms, dust settling, dust getting into places

dust absolutely does not belong. Solar is viable, but it’s not “set it and forget it.”

A realistic Mars power mix

- Solar arrays for daytime baseline power

- Batteries for nighttime and short disruptions

- Nuclear power (like fission reactors) for steady, dust-proof electricity

- Smart grid management to prioritize life support during storms

If you want continuous oxygen production, water extraction, heating, communications, and food growth, you want steady power.

Nuclear systems are often discussed as a serious solution because they’re less dependent on weather and seasons.

Solar can still play a major roleespecially once you have cleaning systems, redundancy, and local manufacturing to replace panels.

Tools, Metals, and Manufacturing: The “Mars Hardware Store” Is a Work in Progress

Living on Mars isn’t just breathing and eating. It’s repairs. It’s spare parts. It’s a broken valve at 2 a.m. when you’d rather not

learn the hard way how much you love oxygen. Local manufacturing is the difference between a resilient outpost and a fragile campsite.

Mars regolith contains a mix of minerals, and researchers have explored extracting useful materials and using regolith in manufacturing.

Early phases will still rely heavily on shipments from Earth, but the direction is clear: the more you can make locallytools,

replacement parts, pipes, brackets, structural componentsthe more “livable” Mars becomes.

The likely progression

- Phase 1: Bring critical spares and use 3D printers for simple parts.

- Phase 2: Use regolith-derived feedstock for more components and shielding structures.

- Phase 3: Develop industrial-scale processing for metals, glass, ceramics, and composites.

Mars doesn’t have a Home Depot. But it might have the raw ingredients for oneeventually.

What Mars Does Not Provide (At Least Not Conveniently)

“Almost everything” is doing some heavy lifting in that headline, so let’s be honest about the gaps.

Mars is helpful, but it’s not hospitable. Major challenges include:

Radiation and a thin atmosphere

Mars lacks a thick, protective atmosphere and global magnetic field like Earth’s, so the surface gets more radiation exposure.

That’s why shieldingregolith, water, or underground habitatsis not optional if you care about long-term health.

Temperature swings and dust

Mars can be brutally cold, and temperatures vary widely by time and location. Dust storms can reduce sunlight and coat equipment.

Habitats need insulation, heating, filtration, and robust maintenance plans.

Low gravity

Mars gravity is about a third of Earth’s. That’s great for moving heavy things and terrible for the long-term biology of humans

(bones, muscles, cardiovascular health). A Mars base will likely require rigorous exercise and possibly future solutions

like rotating habitats for artificial gravitythough that’s not an early-mission feature.

Nitrogen and other “small but crucial” needs

A comfortable habitat atmosphere often includes nitrogen as a buffer gas, and some essential industrial and agricultural processes

depend on elements that aren’t easily accessible. This doesn’t mean Mars is a no-goit means missions must plan for imports,

recycling, and clever chemistry.

So… Is Mars Actually “Livable” With What’s Already There?

If “livable” means “walk outside in a hoodie and breathe deeply,” then no. Mars is not that kind of neighborhood.

But if “livable” means “support a human habitat with local production of key supplies,” the answer gets much more interesting.

The strongest case for Mars settlement is that its resources align with our needs:

CO2 for oxygen and fuel chemistry, water ice for life support and propellant, regolith for construction and shielding,

and sunlight (plus nuclear options) for power. This is why ISRU is such a central theme in human Mars exploration plans.

The planet doesn’t give you comfort. It gives you ingredients.

The most realistic view is this: early Mars bases will be “mostly Earth” in hardware, and “increasingly Mars” in consumables.

Every year, the balance can shiftmore oxygen made locally, more water harvested locally, more structures built from regolith,

more food grown in closed systems. That gradual shift is how “visiting” becomes “staying.”

Conclusion: Mars Is a Supply CacheIf We Bring the Right Tools

Mars is not waiting to welcome us with open arms. It’s waiting like a stubborn puzzle box. But that puzzle box contains

nearly everything we need: oxygen locked in CO2, water stored as ice, abundant regolith for building, and energy sources

that can support the factories and habitats of a small settlement.

The headline promise is both true and incomplete: almost everything we need to live on Mars is already therejust not in the form we’re used to.

If Earth is a fully furnished home, Mars is a construction site with a big pile of materials. The question isn’t whether the materials exist.

The question is whether we can build the systems that transform them into life.

Experience Add-On: What It Might Feel Like to Live Off Mars (A Thought Experiment)

Let’s imagine your first month on Marsnot as a movie montage with heroic music, but as a very practical, very human routine.

This isn’t a personal memory (I don’t have those), but it’s a grounded “day-in-the-life” based on how Mars habitats and ISRU

systems are commonly envisioned.

Day 3: You learn that “air” is now a manufacturing product. Every breath is supported by a chain of equipment:

compressors pulling in thin CO2, an oxygen generator humming like a determined toaster, sensors checking purity,

and storage tanks that feel weirdly precious. On Earth, you inhale without thinking. On Mars, you inhale and silently thank the engineers.

Week 1: Water becomes your favorite topic. Not in a “stay hydrated” way, but in a “this is literally our lifeline” way.

Someone shows you the ice-handling workflow: locate, drill, collect, melt, filter, store. It feels like running a tiny municipal utility,

except the “city” is a handful of people and the “utility” is your survival. Showers are short. Dishwashing is strategic.

You’ve never respected a clean cup so much in your life.

Week 2: You discover the psychological magic of green things. The greenhouse is warm, bright, and smells faintly alive.

Even if the crops are mostly practicalleafy greens, herbs, maybe some compact dwarf varietiesit feels like a pocket of Earth.

People linger there longer than necessary, pretending they’re “checking growth metrics” when they really just want to see something that isn’t red dust.

Fresh food becomes a morale system as much as a calorie system.

Week 3: Construction day. You watch a rover push regolith into berms around the habitat like it’s landscaping,

except the landscaping is radiation shielding. Someone jokes, “Welcome to the Homeowners Association,” and everyone laughs a little too hard.

You learn how the base keeps dust out: airlocks, filters, careful suit procedures, and constant cleaning. Mars dust is not just “dirty.”

It’s persistent, fine, and determined to join every moving part in your life.

Week 4: You get your first “Mars problem.” A valve sticks in a system that matters. On Earth, you’d call maintenance.

On Mars, you are maintenance. The base shifts into calm checklist mode: isolate the line, verify pressure, swap the part,

test again, log the fix. The emotional rhythm is strange: you feel stress, then pride, then a quiet appreciation for redundancy.

Living on Mars teaches you that resilience isn’t a personality traitit’s infrastructure.

Over time, you start thinking differently. You stop seeing the planet as hostile scenery and start seeing it as a resource map.

That ridge? It might shade solar panels in winter. That area? Better for ice access. That regolith pile? Potential shielding.

Mars becomes less like a destination and more like a system you participate in.

And here’s the subtle part: when your oxygen comes from the air outside, your water comes from ice underground, and your shelter is protected

by the dirt around you, you feel something surprisingly intimate with the environment. Not romanticMars is still trying to freeze youbut connected.

The planet isn’t “home” in the Earth sense, yet. But it starts to feel like a place where humans can build continuity, day by day,

using what’s already there.